In August 1735, John Hele, the Librarian, discovered that some books were taken out or stolen from the Library. Book theft would not have been a strange occurrence to the Library; in fact, during the early eighteenth century, the books of the Library were often chained to their cupboards to prevent them from being taken away. With just six books reported to be missing, the theft might not have seemed a particularly heinous one.

Note recording the books missing in the Library, 1735 (MT/9/LMF/70/1)

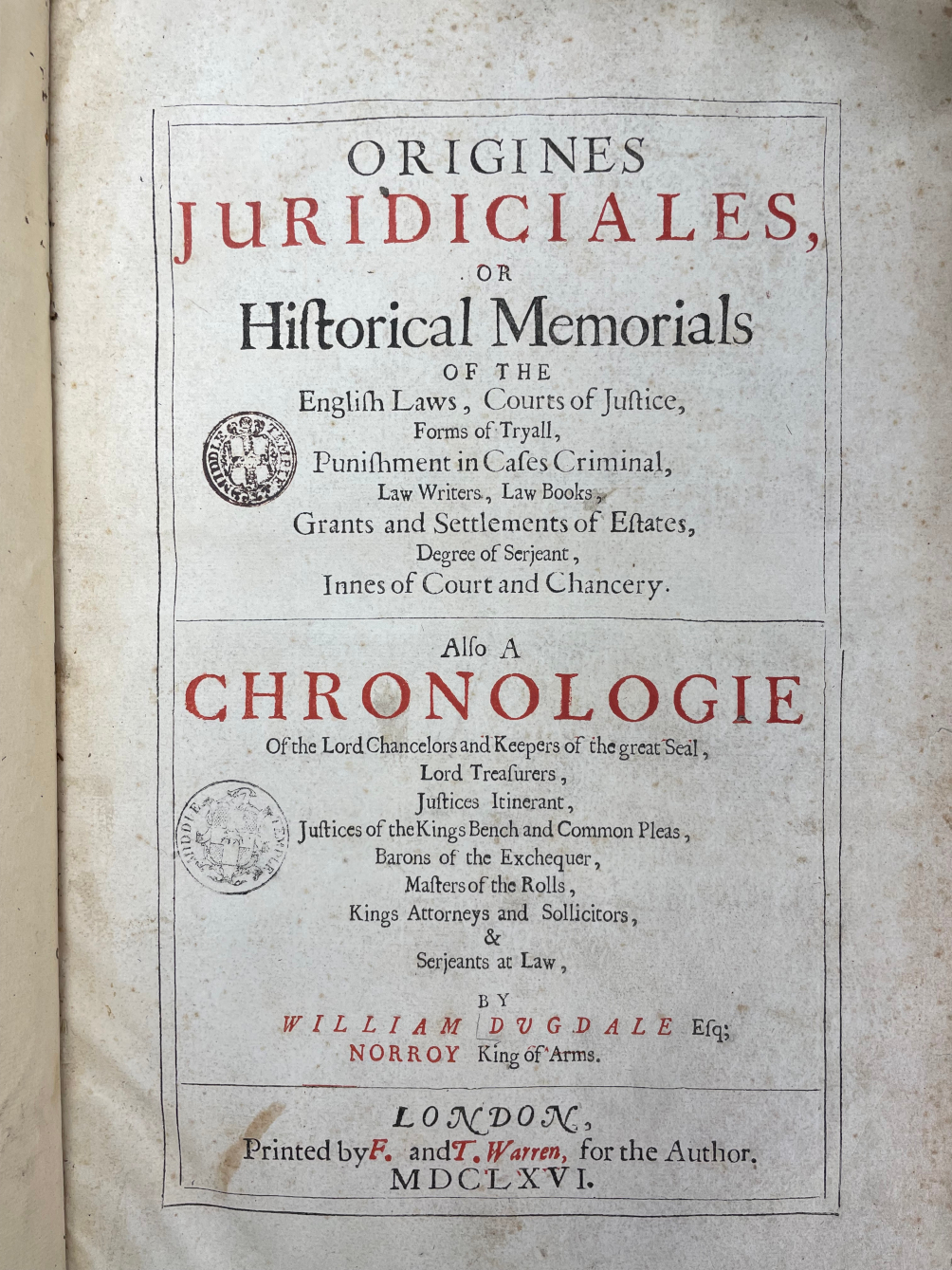

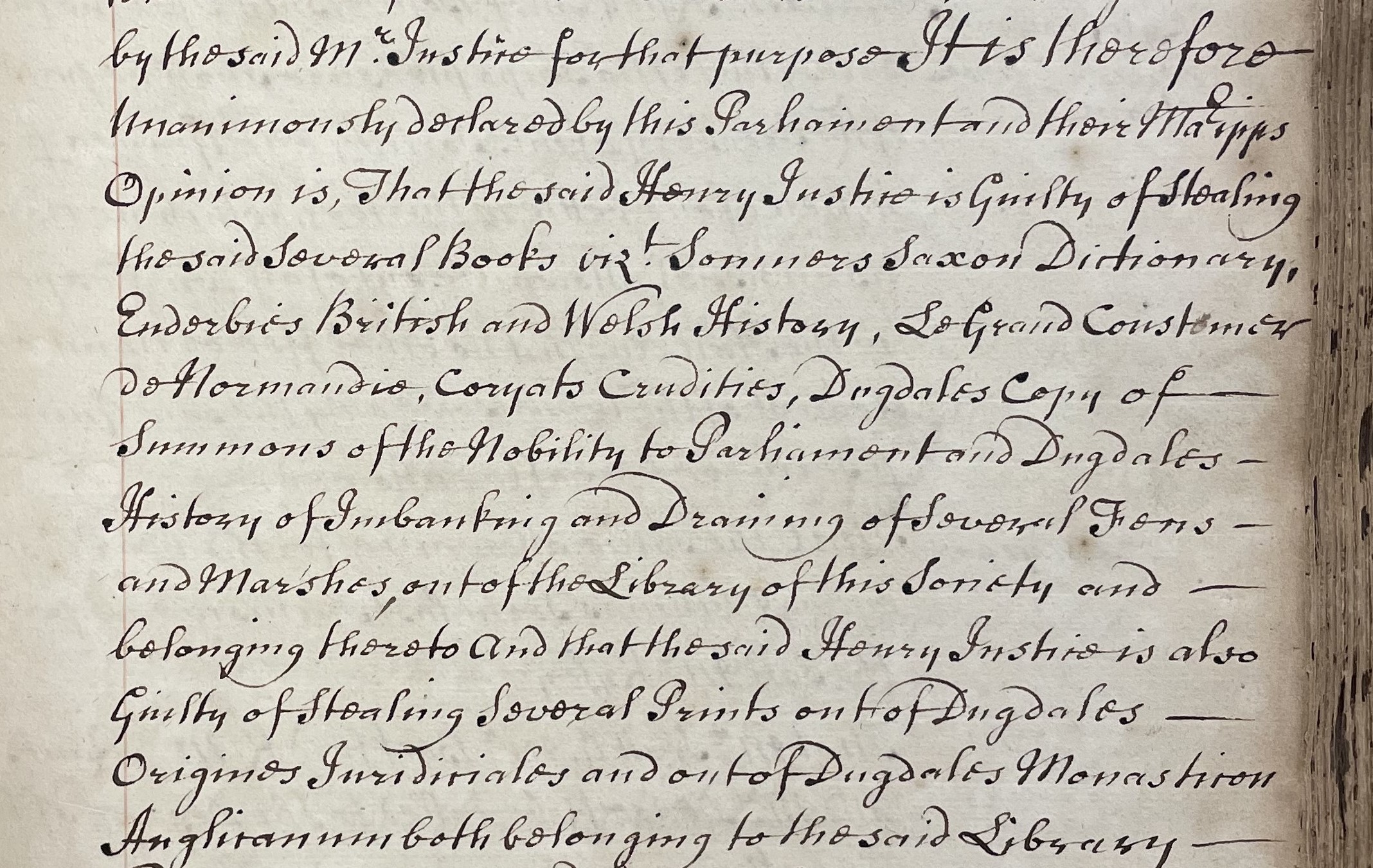

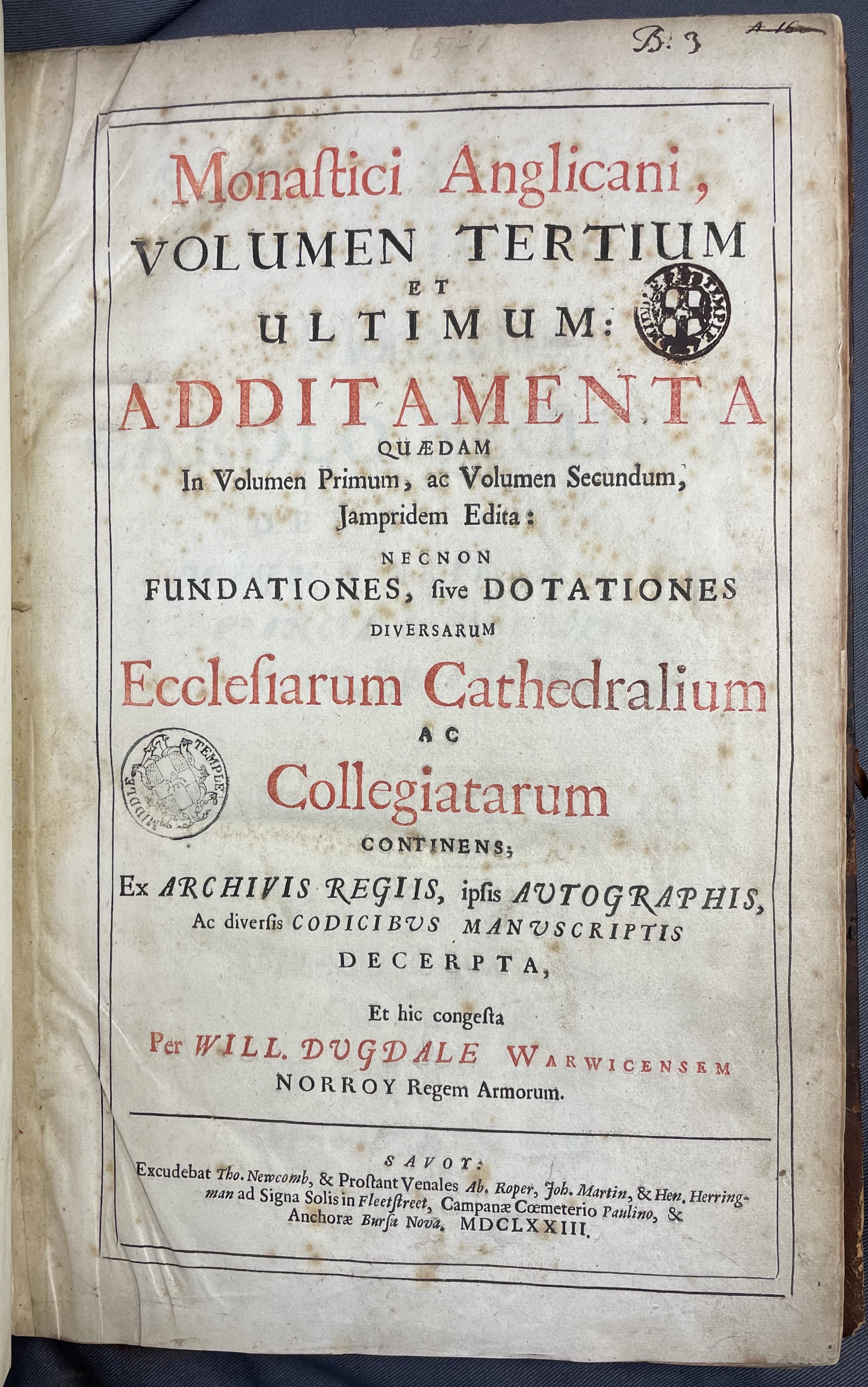

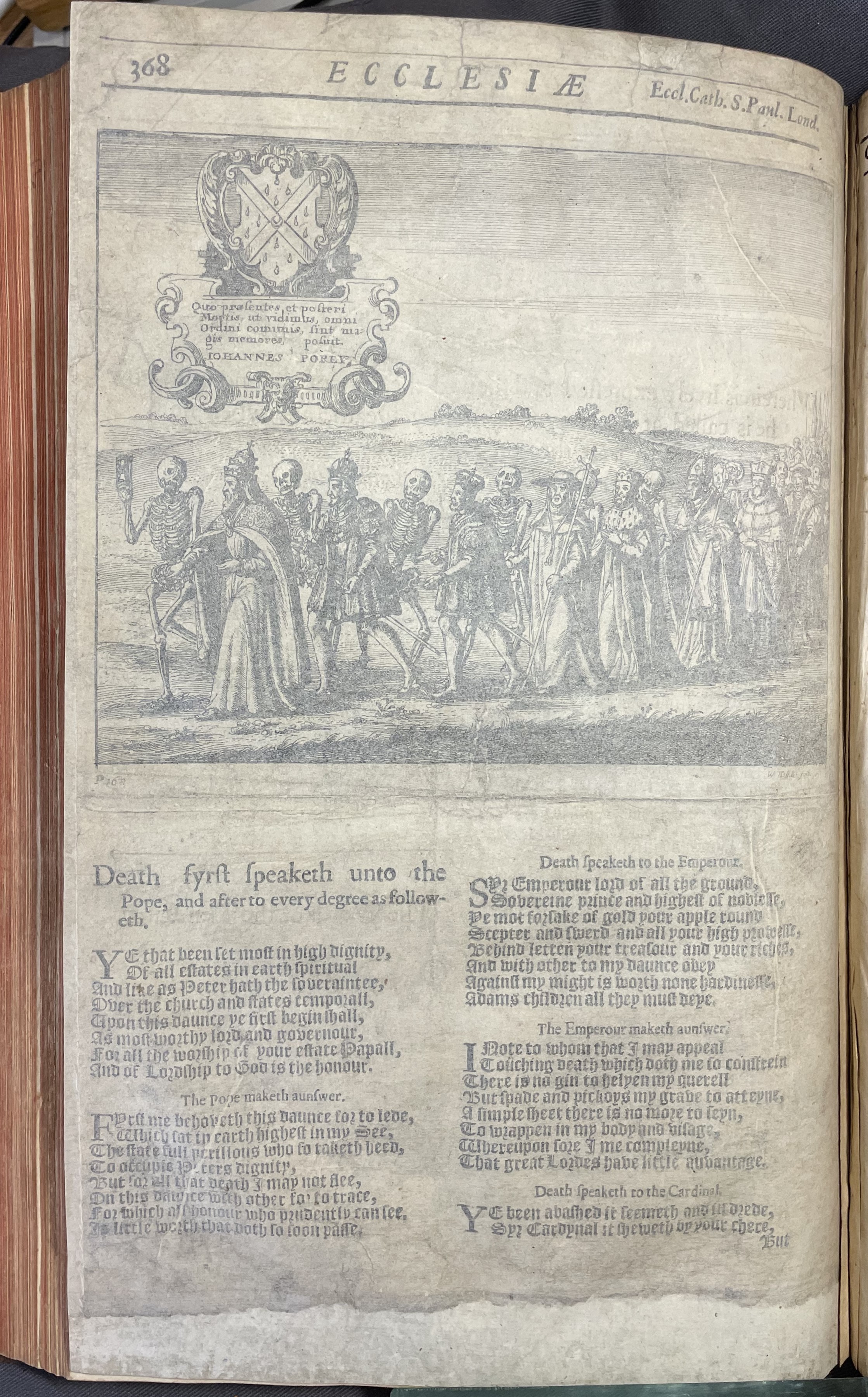

The thief seems to have had a diverse taste for books, as the volumes stolen cover a range of subjects from history to heraldry, and from dictionary to travelogue, including two titles by Sir William Dugdale, a medievalist scholar and officer of the College of Arms. In addition, the Library's copies of Origines juridiciales and several volumes of Monastici Anglicani, both also by Dugdale, were found to have had prints cut out from the volumes.

William Dugdale, depicted as the Norroy King of Arms at the funeral of the 1st Duke of Albemarle in 1670 (MT/19/POR/226)

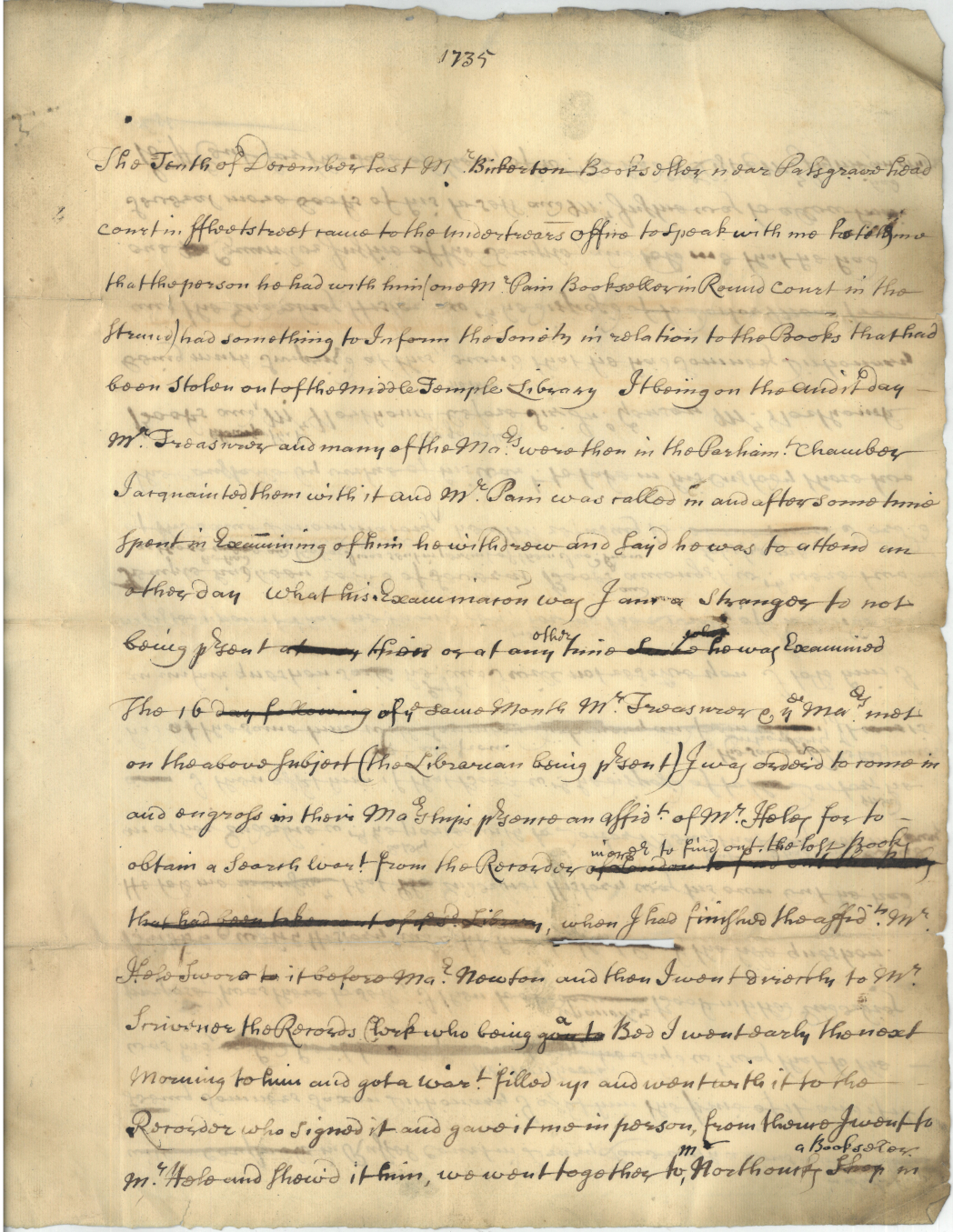

Hele had little success tracking down the books until 10 December, when a bookseller called Mr. Paine brought the news that ‘two books of the like sort’ were being advertised by another bookseller, Harmen Northouck, in Drury Lane. The Covent Garden area bordered by Drury Lane was then the home to a thriving network of those involved in the book trade, including booksellers and bookbinders. Mr. Paine was brought to see the Under Treasurer of the Inn, Richard Bruncker and, after an examination by the Masters of the Bench, the Inn decided to send Bruncker and Hele for some sleuthing.

Copy of the affidavit regarding the theft by John Hele, the Library Keeper (MT/9/LMF/70/1)

Bruncker and Hele were well-prepared for their visit to Northouck’s bookshop. Acting on Mr. Paine’s tip-off, Hele produced an affidavit detailing the theft – this document was then shown to Sir William Thompson, the Recorder of London, on 16 December, by Bruncker. Having read Hele’s affidavit, Sir William issued a search warrant granting Bruncker the right to search for and procure the lost books. That same day, Bruncker and Hele, accompanied by a constable, headed off to the bookshop.

Search warrant issued by Sir William Thompson, 16 December 1735 (MT/9/LMF/70/1)

At the bookshop, Bruncker quickly noticed the two missing titles: William Somner’s Saxon-Latin-English dictionary and Percy Enderbie’s volume on British and Welsh histories. Upon Bruncker’s tactful interrogation, Northouck revealed that Enderbie’s volume was his personal copy, but admitted that the dictionary was to be sold on behalf of someone, whose identity he was at first reluctant to disclose. Bruncker invoked the power authorised to him to compel Northouck to cooperate, as he wrote in his account:

I ordered the constable by virtue of his warrant to take in his custody those two books ... Mr. Northouck, being much surprised at this, then owned that he had Somner’s Dictionary and the Enderbie’s History, which he disposed of to Doctor Mead [possibly Doctor Richard Mead, physician appointed to George II], from one Councilor Justice of the Temple, and told me that he had several more books of his to sell and Mr. Justice was to allow him ten percent for the sale of them.

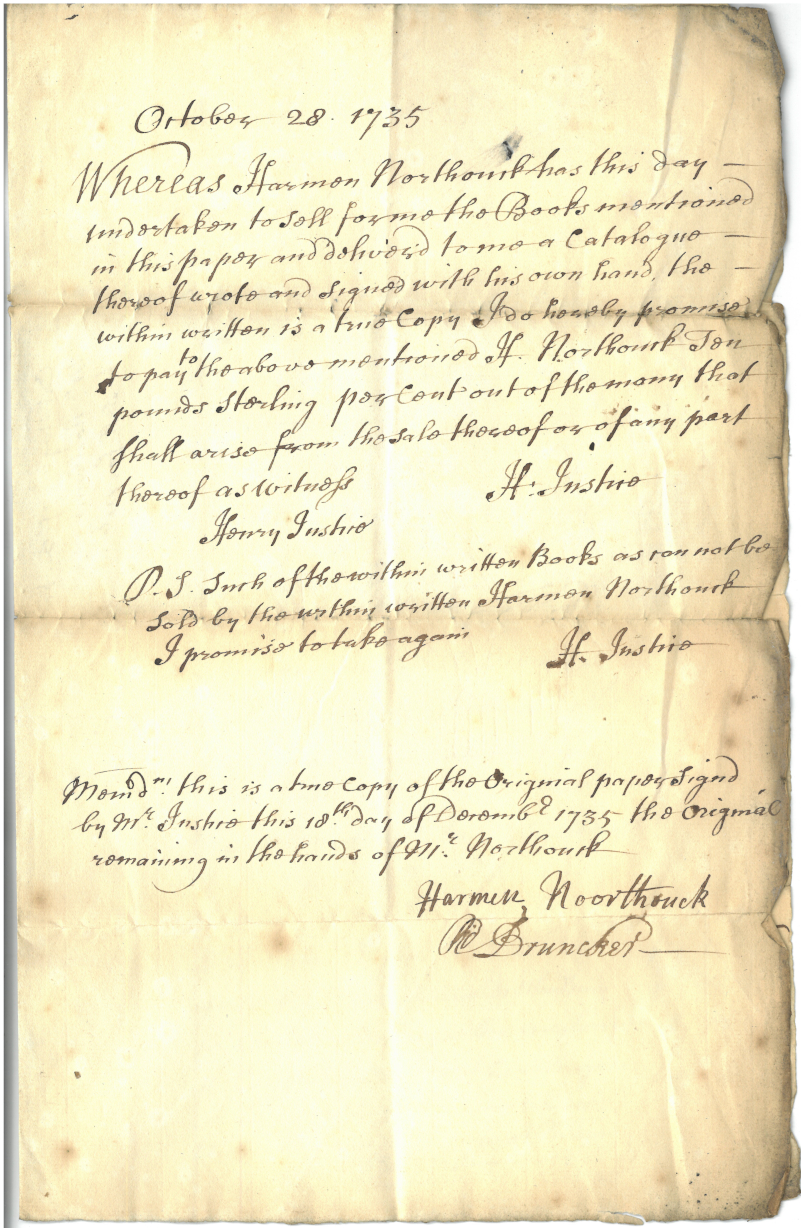

During their investigation, a list of nearly 30 books consigned to Northouck was discovered, and Bruncker later made a copy for the record. It was also found that another bookbinder, John Robignor, along with his journeyman, John Churchill, were involved in binding those books.

Extracts of copy of the catalogue made by Harmen Northouck for the books consigned to him in October, 18 December 1735 (MT/9/LMF/70/2)

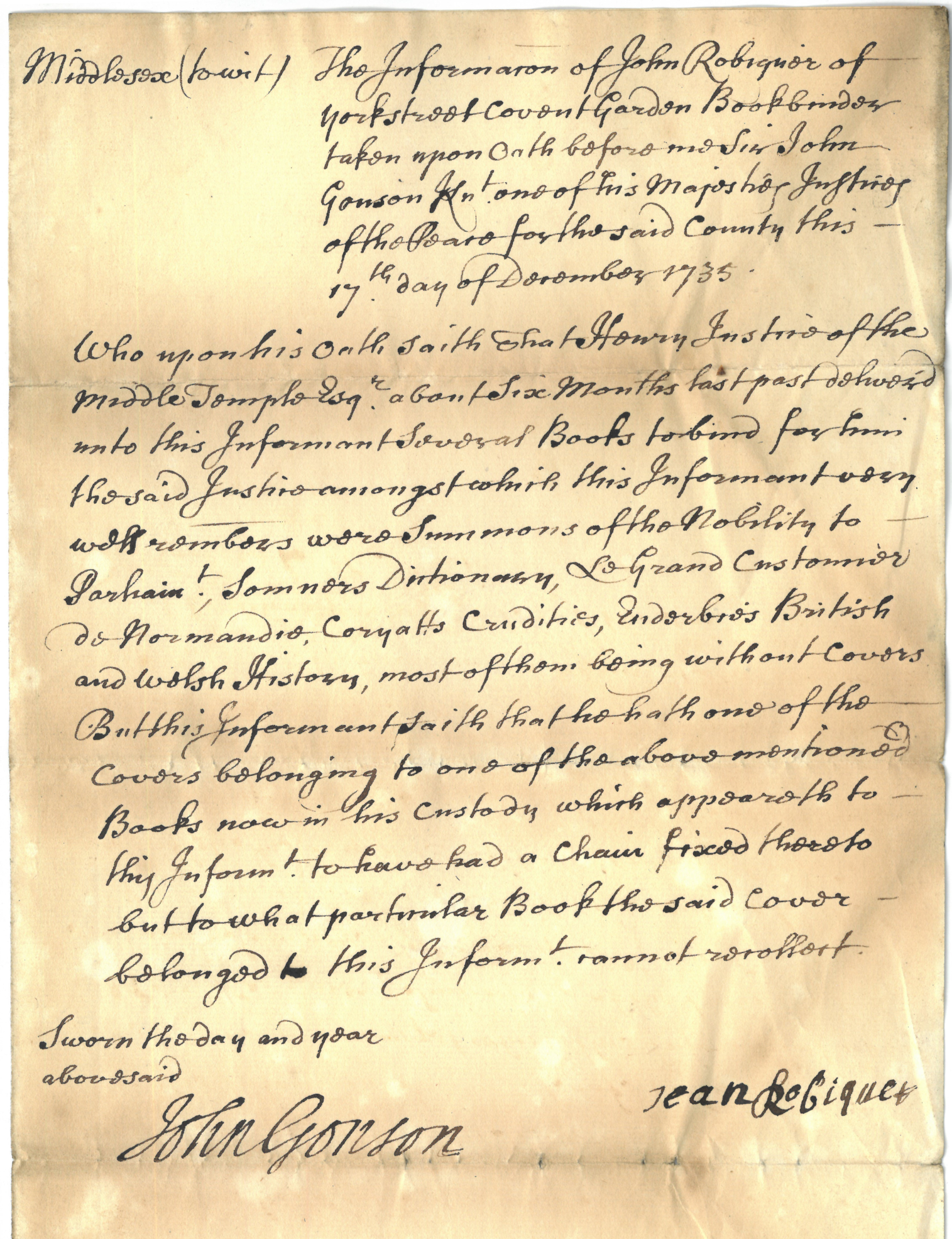

On the next day the bookseller and bookbinders appeared before Sir John Gonson, Justice of the Peace for the City of Westminster, to give a sworn testimony. The movement of the missing books now became clearer: Robignor confessed that around six months ago he had received copies of the missing titles from Justice for binding, most of which were without covers, while one cover ‘appeared to have had a chain fixed thereto’. These books were then passed to Churchill, who bound and brought them to Justice’s chambers in Temple. Northouck also recalled that on 28 October Justice delivered him the two books by Somner and Enderbie to sell in his bookshop.

Affidavit by John Robignor, bookbinder, 17 December 1735 (MT/9/LMF/70/2)

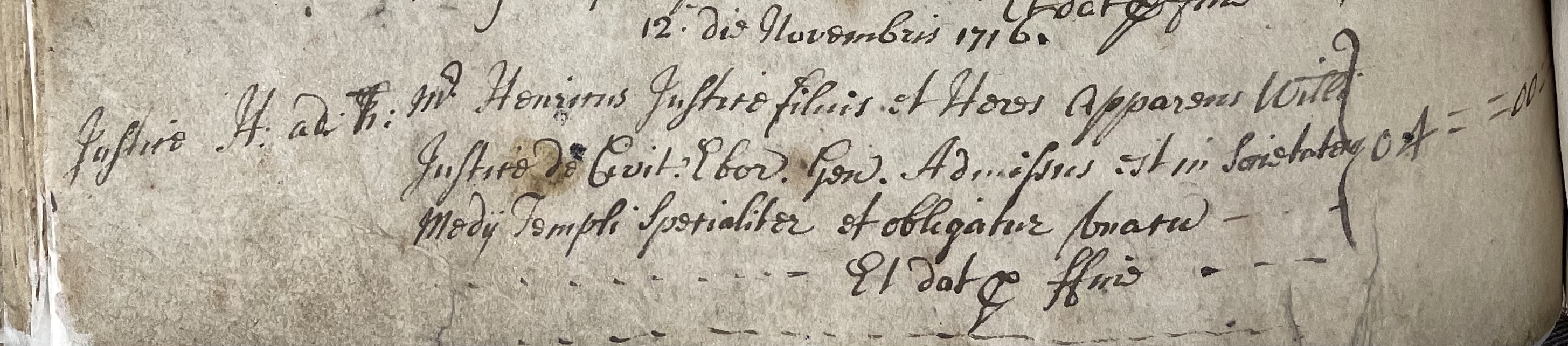

The ‘Mr. Justice’ in question was Henry Justice, a barrister of Middle Temple. Son of an attorney, he became a pensioner (a fee-paying student) at Trinity College Cambridge at the age of 19, shortly before his admission to Middle Temple on 12 November 1716. He was Called to the Bar by the Inn on 10 February 1727. Beyond those relating to this incident, few archival records remain relating to Justice’s time at the Inn, but a surviving bond suggests that after his Call he was admitted to a chamber in a new building on the south side of Garden Court.

Extract of admissions volume showing the admission entry of Henry Justice, 12 November 1716 (MT/3/AHC/2)

However, Justice must have moved his dwelling since then, as his chamber was in Elm Court when he was summoned to see the Masters of the Bench in the last week of December 1735 for an enquiry. Bruncker recorded that Justice acted defensive during the enquiry:

Justice told the Masters he did not know what this enquiry tended to, and why they should suspect him more than any other members of the society. ... he believed he might have some of these sort of books ... and he was sure he could satisfy them where he bought them, and that he had perhaps as good a Library as any private gentleman in England had.

The actual search for the books was documented in detail by the Under Treasurer – it is recorded that Bruncker had to go up three times to Justice’s chambers during the search. Several volumes were found at the scene, including Coryat's Crudities, Le Grand coustumier du pays et duché de Normendie, and A Perfect Copy of All Summons of the Nobility to the Great Councils and Parliaments of this Realm. Bruncker also spotted Justice’s copy of Origines juridiciales, which only came into his possession after a struggle, as Justice reportedly snatched it from his hands before eventually relenting.

Extract of the account on the theft by Richard Bruncker, the Under Treasurer, December 1735 (MT/9/LMF/70/3)

The next Tuesday the Masters of the Bench held another meeting to examine the books thoroughly. Bruncker recorded that there was some difficulty in determining whether the copies found in Justice’s chambers indeed belonged to the Library, as the books lacked the Library's shelfmarks. For Somner’s dictionary and Dugdale’s Summons of the Nobility, one of them was said to have a corner of the title page cut out and the other the page facing the title page completely torn out – these are where such markings would typically have been written by the Librarian.

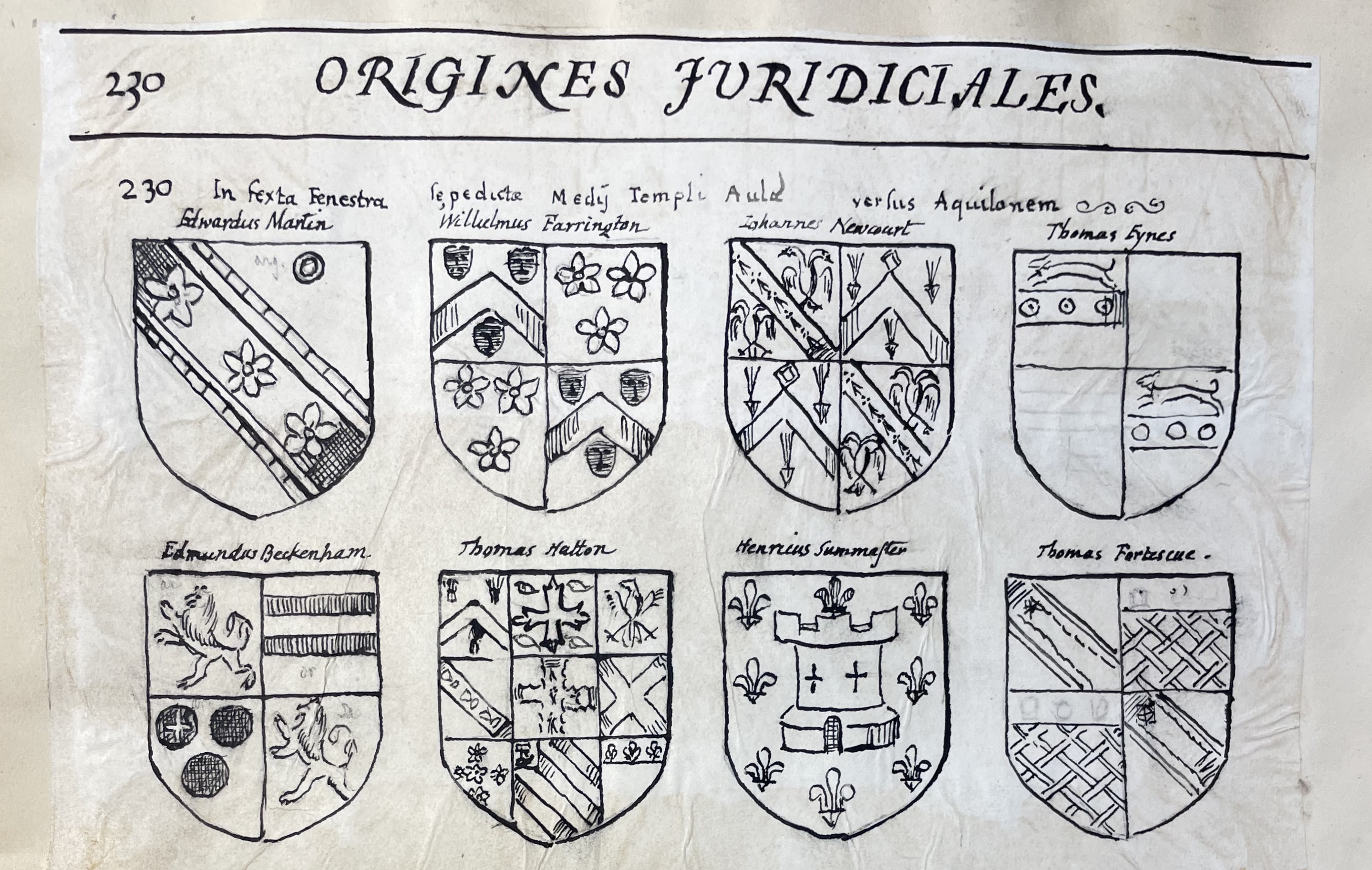

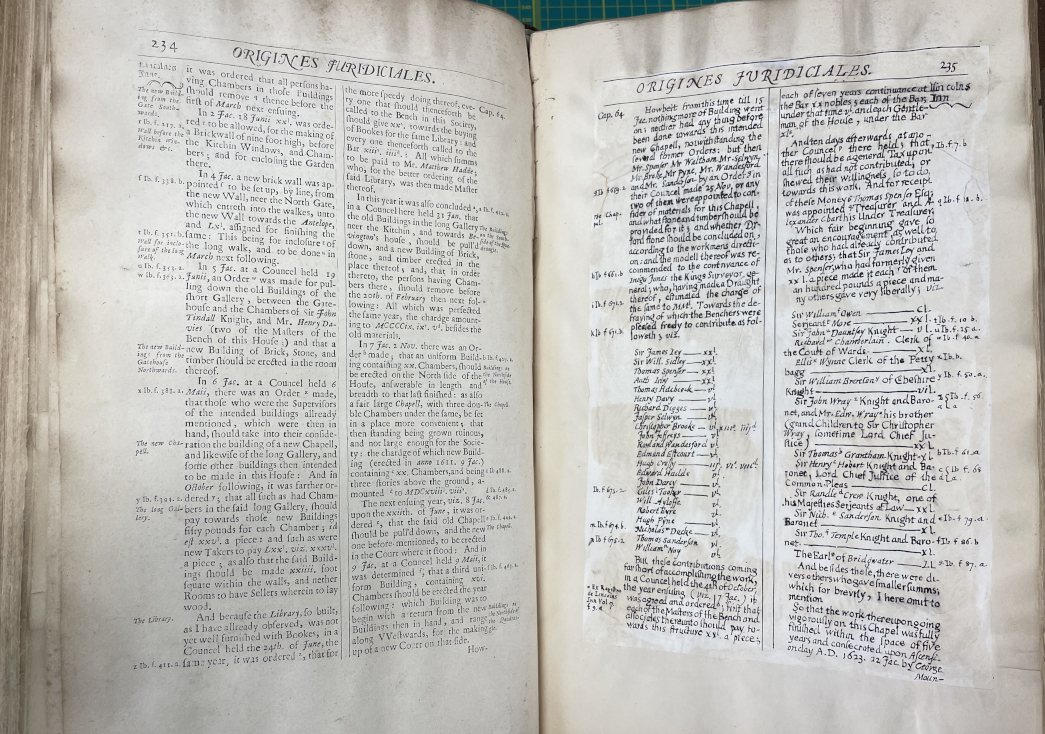

Justice might be clever enough to destroy the markings, but his copy of Origines juridiciales betrayed him. A title charting the development of English laws and its legal system and education, Origines juridiciales features engravings of the coats of arms of prominent individuals, some of which can still be seen in Middle Temple Hall today. On comparing Justice’s copy with the defaced copy in the Library, the Masters of the Bench noted that his copy ‘was of a thin common paper and theirs of thick royal paper’ and that the pages with engravings were ‘much thicker than his other leafs were, and better colour.’ This suggests that the engravings had been inserted into Justice’s lower-quality copy.

Title page of a 1666 copy of Origines juridiciales held by the Middle Temple Library

After the investigation, Parliament resolved on 23 January 1736 that Justice was guilty of stealing and defacing books owned by the Library. The Inn might have considered prosecuting Justice for the theft, but what happened during the interval led them to pause any legal action. The theft at the Library alerted Trinity College Cambridge, who, having realised books were also missing from their library, followed the Inn’s action to search Justice’s chambers on 7 January 1736. Some sixty books and tracts bearing the College arms and the library’s marks were found, and Justice, who appeared to have stolen them, now faced prosecution by the College.

Extract of the minute of Parliament recording that Henry Justice was guilty of the theft, 23 January 1735/6 (MT/1/MPA/7)

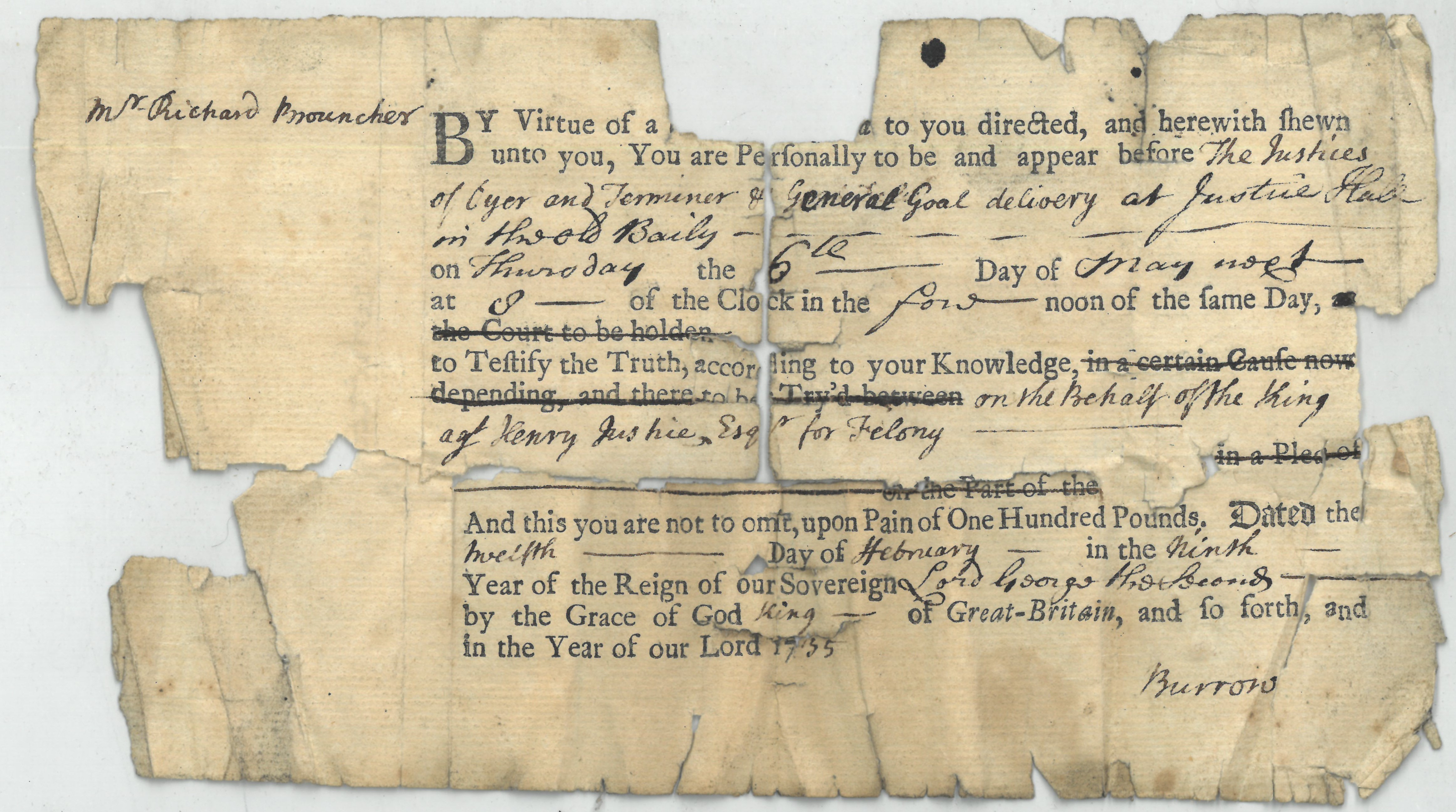

Following this second search, Justice was detained in Newgate Prison until 5 May 1736, when he was tried for theft and grand larceny at the Old Bailey. Although the trial concerned Justice's theft at Trinity College Library rather than Middle Temple Library, Bruncker likely attended it as there is a printed order requiring him to be present and give a testimony. Justice represented for himself in the trial (an account of the trial is available here) and claimed that as a Fellow Commoner of the Trinity College, he was allowed to take the books out of the College's library. His argument does not seem to have convinced the jury, who eventually found him guilty. In his final plea for mercy, Justice insisted his innocence:

I solemnly declare, that I did charge the Librarian to put them to my account. If a man goes and takes a book according to the Rules of the College, and orders the book to be set down, if it should be neglected, no gentleman can be safe: I mention this that they may take more care, and that accidents of this kind may be prevented for the future.

Order addressed to Richard Bruncker to appear before the trial of Henry Justice to give a testimony, 12 February 1735/6 (MT/21/1/122)

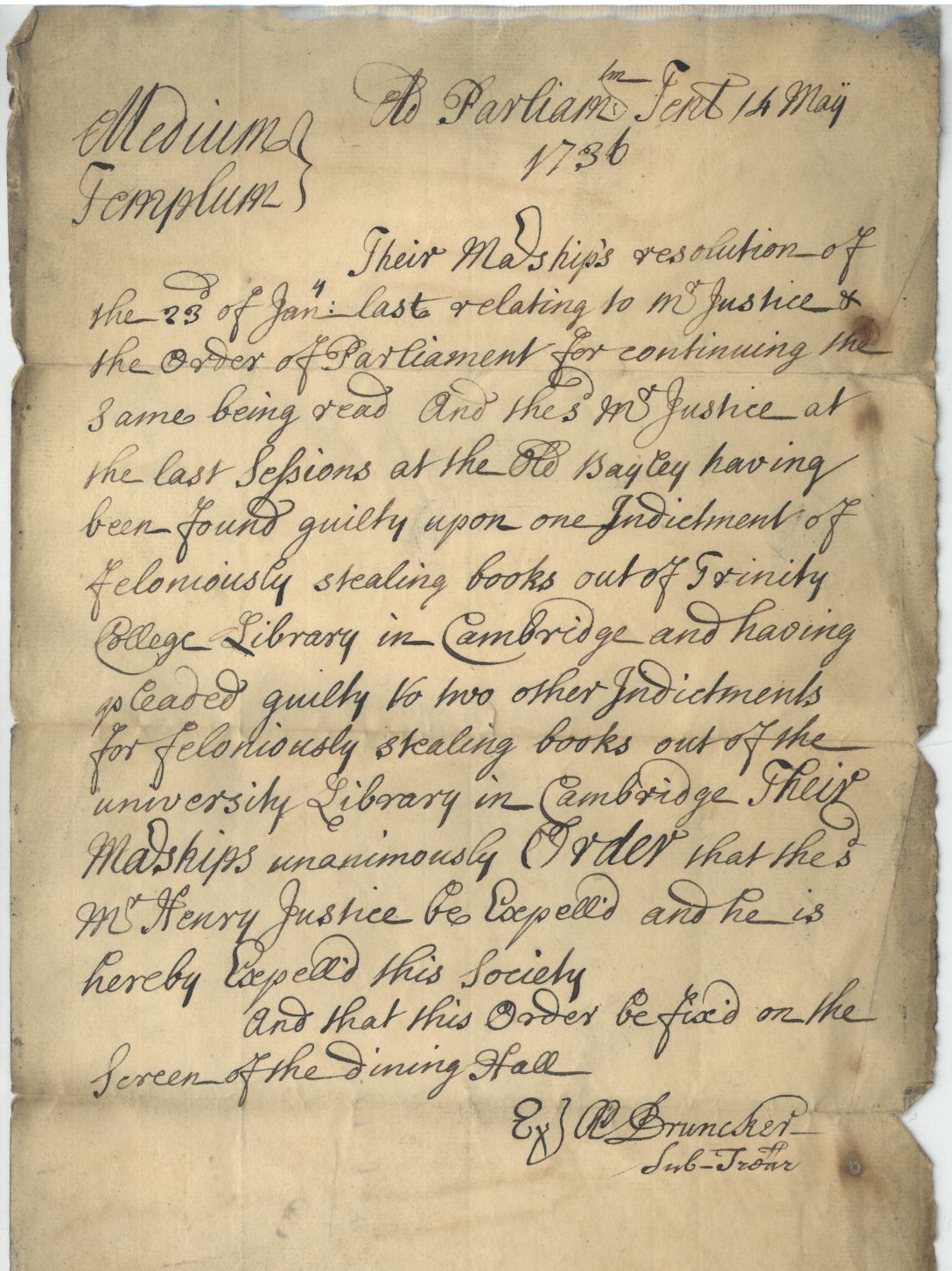

On 10 May Justice was sentenced to seven years’ transportation to America. Four days after the judgement was announced, Parliament unanimously ordered his expulsion from the Inn.

Copy of the order by Parliament to expel Henry Justice, signed by Richard Bruncker, 14 May 1736

But what became of the books missing from Middle Temple Library? Enderbie’s volume was said to have been sold by Northouck before the investigation, so it might have never been recovered. The records do not give a clear indication that other books were returned to the Library after the investigation either. Even if they were, some unfortunately went missing again later. The Library to this date still holds in its collection copies of the same editions of Somner's dictionary, Le Grand coustumier du pays et duché de Normendie, and Summons of the Nobility that were involved in the incident; however, insufficient provenance information added to the challenge of ascertaining whether they are the same copies.

Extract of a catalogue recording the books missing in the Library, 1817 (MT/9/LMV/1)

But there is reason to believe that the Library might still hold the same copies defaced by Justice. Of the two copies of Origines juridiciales (1666) in the Library, one is missing some of the original engravings. A manuscript bookplate dated 1899 in this copy shows that the Librarian manually copied the missing engravings as well as any text on the pages to reconstruct a complete copy. Additionally, two volumes of Monastici Anglicani, dated 1661 and 1673, part of a three-volume work tracing the history of monasteries and churches in England and Wales, have most of the engravings missing as well.

A 1666 copy of Origines juridiciales held by the Library, showing manually copied coats of arms, including those of Middle Temple members

A 1666 copy of Origines juridiciales held by the Library, showing an original printed page facing a manually copied page

A 1673 copy of the third volume of Monastici Anglicani held by the Library, showing the title page (left) and a surviving engraving (right)

Although the recently catalogued archival records give some dramatic details of the incident, a lot of mystery surrounding the theft remains unresolved, particularly the whereabouts of the missing books. What we can be sure of, somewhat regrettably, is that Henry Justice was not the first, still less the last, book thief that Middle Temple Library had seen in its long history. Similar thefts were to happen in the later centuries, adding more thrilling narratives to the Library’s storied past.