The British people are well known for their preoccupation with the weather, to the extent that it is considered a ‘national obsession’ - the unpredictable climate of the British Isles providing a constant topic of casual discourse for their inhabitants. Prior to the invention of central heating, air conditioning and modern roads, changes in weather conditions had an even greater impact on people’s day-to-day lives, however, only a small portion of peoples’ daily struggles can be found in the archival record. Discussion of weather and climate generally occurs in the Inn’s administrative records when it has caused some sort of problem or when event has had an impact on business-as-usual, skewing recording towards the more extreme instances of weather.

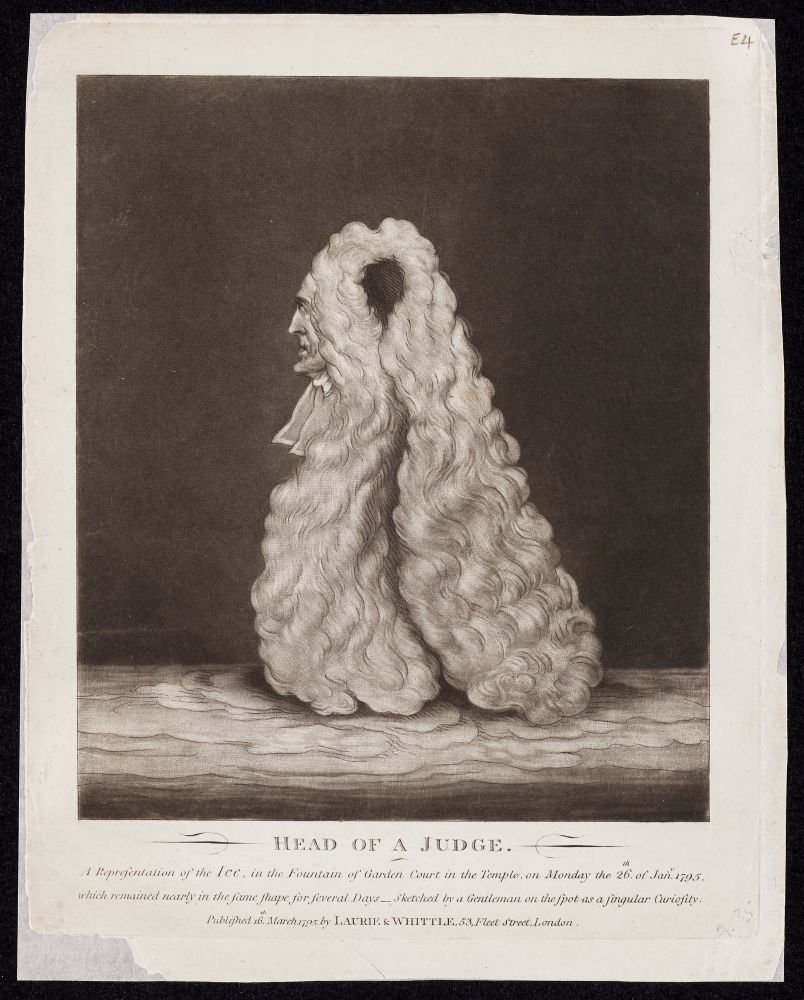

An ice sculpture of the Head of a Judge in the Middle Temple’s Fountain ‘sketched by a Gentleman on the spot as a singular curiosity’, 26 January 1795 (MT/19/ILL/E/E4/11)

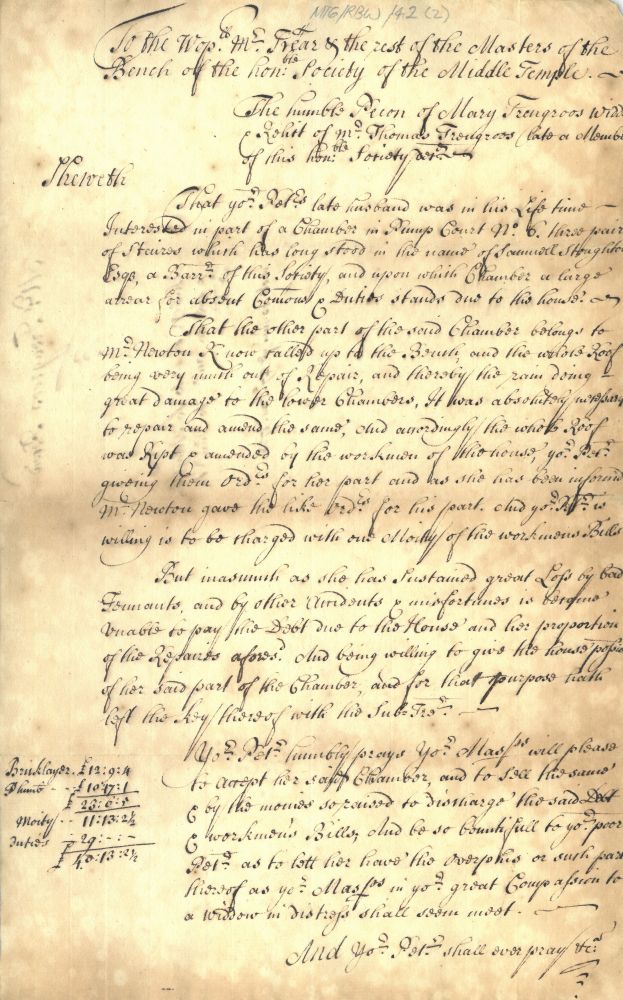

Quality of life during the cold, damp part of the year can be either enhanced or destroyed by the conditions of a person’s living space. Unfortunately, the Inn’s chambers haven’t always been kept in good repair over the course of the Society’s history. In the eighteenth century, the Inn’s chambers were usually granted to tenants who would commonly sublet their chambers to members. These tenants would also be responsible for financing repairs, which sometimes left chambers in bad condition due to neglect. One petition to the Inn’s parliament is from Mary Trengroos, who inherited a life interest in 6 Pump Court from her husband. She asked to be allowed to sell her interest as she had incurred great debts due to having to repair the whole roof – she and the other assignee, Master Newton, probably stalled these necessary works as long as possible as, by the time of the petition, the rain had been doing great damage to the chambers and this would not have occurred if repairs had been completed in a timely manner. One can only imagine the misery endured by the inhabitants of 6 Pump Court until the repairs were completed – forced as they were to live in cold, damp chambers. A subsequent petition dating to 1745, also referring to 6 Pump Court, states that the front rooms did not even have fireplaces ‘which renders the Chambers of very little use, especially in the winter season’.

Petition from Mary Trengroos to allow the sale of her life interest in 6 Pump Court, c.1723 (MT/6/RBW/42)

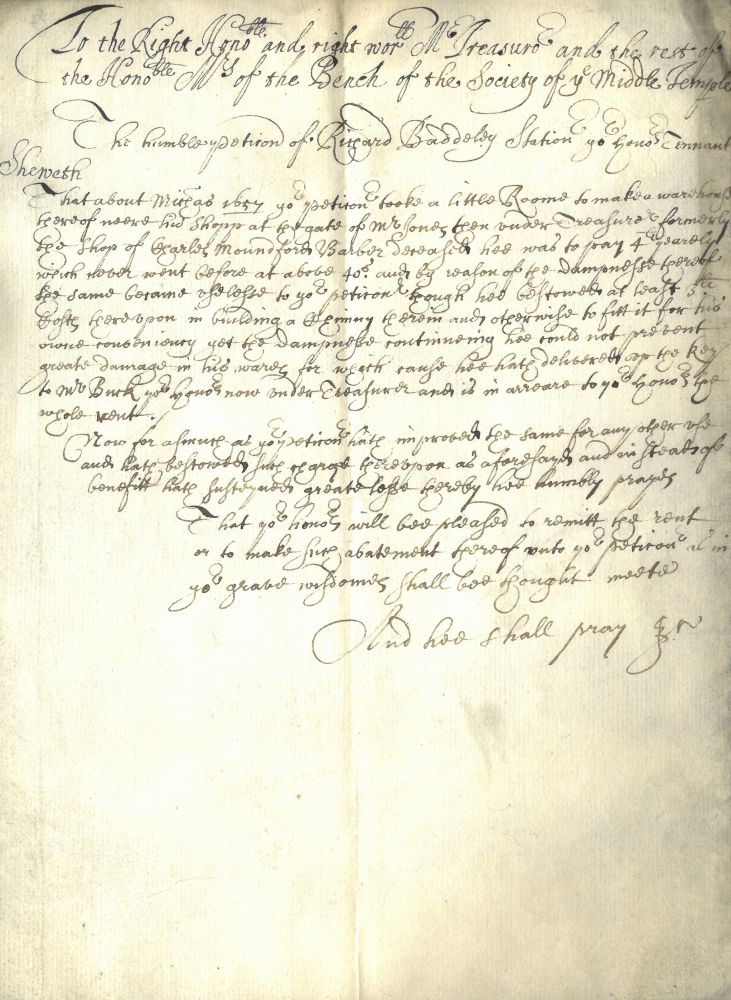

The Inn’s tenant tradesmen also suffered problems caused by the cold, damp climate. A petition submitted to the Inn’s Parliament in 1663 from Richard Baddeley, stationer, requested an abatement of the rent of a room he had intended to make into a warehouse for his stock. The room had proved too damp to use despite Baddeley adding a chimney and fireplace at his own expense, a common addition requested and financed by uncomfortable tenants, and his wares had been damaged by the damp. He subsequently delivered the room key back to the Under Treasurer, having given up on his plans, the unfortunate damp problem having cost the Inn a paying tenant.

Petition of Richard Baddeley, stationer, for an abatement of rent due to damp damaging his wares, c.1663 (MT/5/SHO/12)

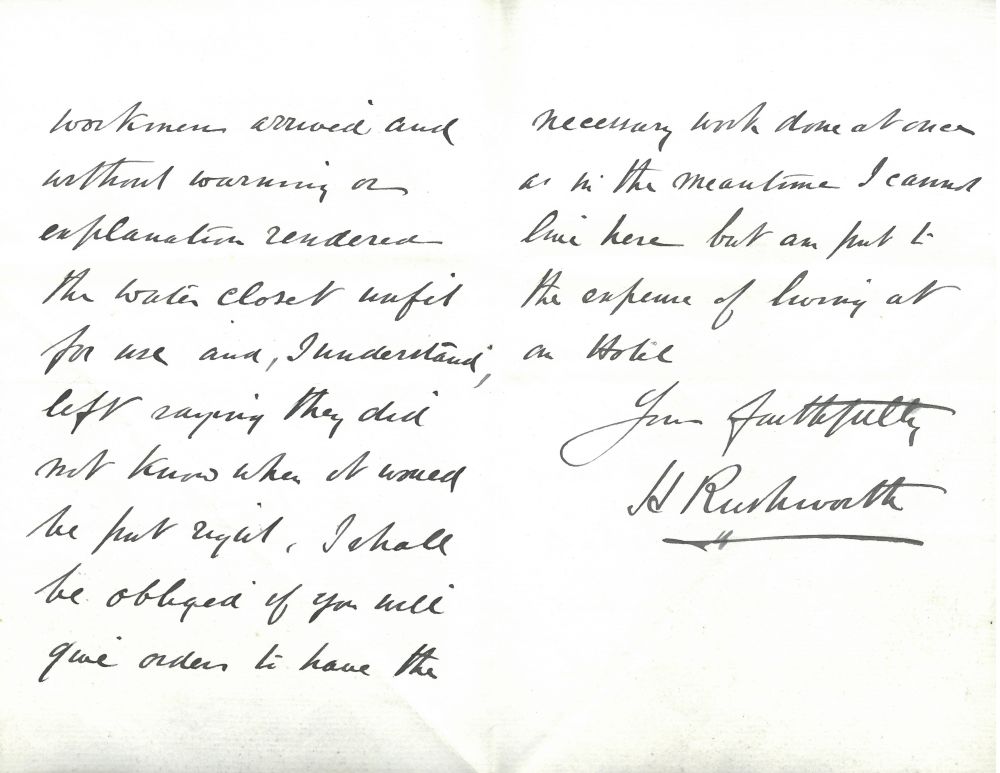

As well as enduring unpleasant temperatures during the winter, the Inn’s inhabitants had to wrestle with the practical difficulties caused by these conditions. After water pipes were installed at the Inn, this included problems with frozen pipes and a resulting lack of water supply, as shown by a letter of complaint from H. Rushworth, a tenant of 4 Brick Court, written on 24 February 1895. He wrote ‘I have been a fortnight without a water supply; now that the thaw has come matters appear to be even worse – In my absence yesterday morning, workmen arrived and without warning or explanation rendered the water closet unfit for use and, I understand, left saying they did not know when it would be put right’. A note written the 26 February on the corner of the letter sheds light on the matter, stating the water closet had been damaged by the freezing temperatures and that, happily for Rushworth, everything had been put right.

Letter from H. Rushworth of 4 Brick Court regarding the interruption of his water supply due to frozen pipes, 24 February 1895 (MT/21/1/23/6/8)

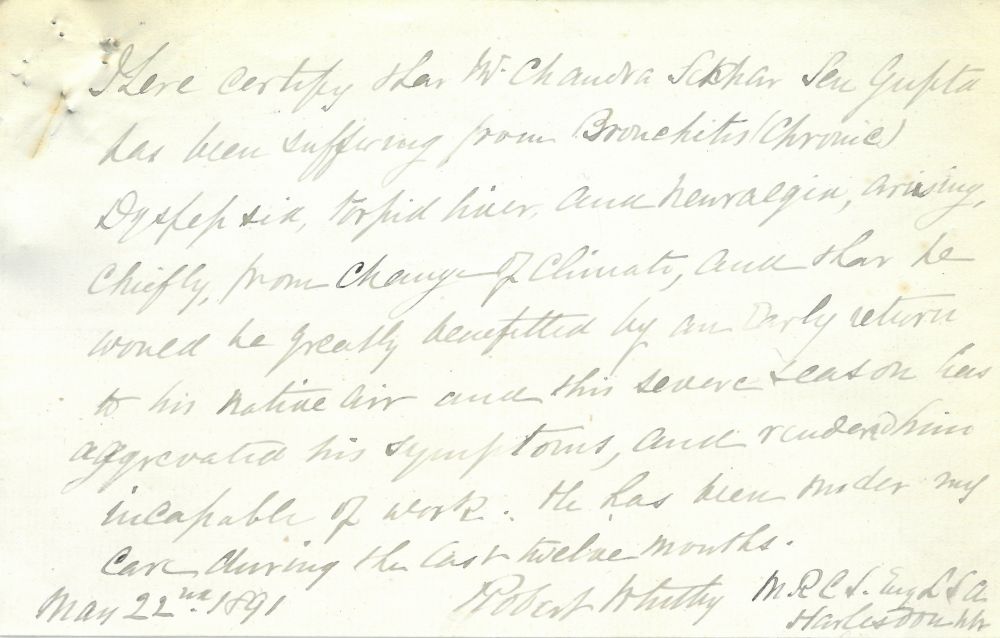

The inhabitants of London did not allow extreme weather to dampen their spirits, despite the biting cold. Due to the wider, shallower and slower flowing River Thames and the phenomenon known as the Little Ice Age, a period of colder climate from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the Thames froze over, though infrequently. Great fairs were held on the ice until as late as 1814. A copy of a print of a frost fair during the reign of Charles II shows the fair at the base of the Temple Stairs, a pier that used to belong to the Society prior to the creation of the Victoria Embankment in the 1860s, and are at the far left of the image. Three figures walk over a precarious plank of wood to move from the icy river back to the relative safety of Middle Temple Lane – during the 1684 fair, Temple Stairs led directly to the main street of the Frost Fair, known as Temple Street, which existed only as long as the ice remained.

Copy print of a Frost Fair on the Thames during the reign of Charles II (MT/19/ILL/F/F5/11)

The famous writer, gardener and diarist John Evelyn describes the festive activities of the 1684 fair– ‘The frost continues more and more severe, the Thames before London was still planted with booths in formal streets, all sorts of trades and shops furnished, and full of commodities, even to a printing press... Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple, and from several other stairs to and fro, as in the streets, sleds, sliding with skates, a bull-baiting, horse and coach-races, puppet-plays and interludes, cooks, tippling, and other lewd places, so that it seemed to be a bacchanalian triumph, or carnival on the water…’

Map of the Frost Fair on the Thames, 1684 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Evelyn also speaks about the effect of the extreme cold on the city – ‘London, by reason of the excessive coldness of the air hindering the ascent of the smoke, was so filled with the fuliginous steam of the sea-coal, that hardly could one see across the street, and this filling the lungs with its gross particles, exceedingly obstructed the breast, so as one could scarcely breathe. Here was no water to be had from the pipes and engines, nor could the brewers and divers other tradesmen work, and every moment was full of disastrous accidents.’

Fountain Court in the snow, looking towards Middle Temple Lane, c.1935 (MT/19/PHO/10/14/5)

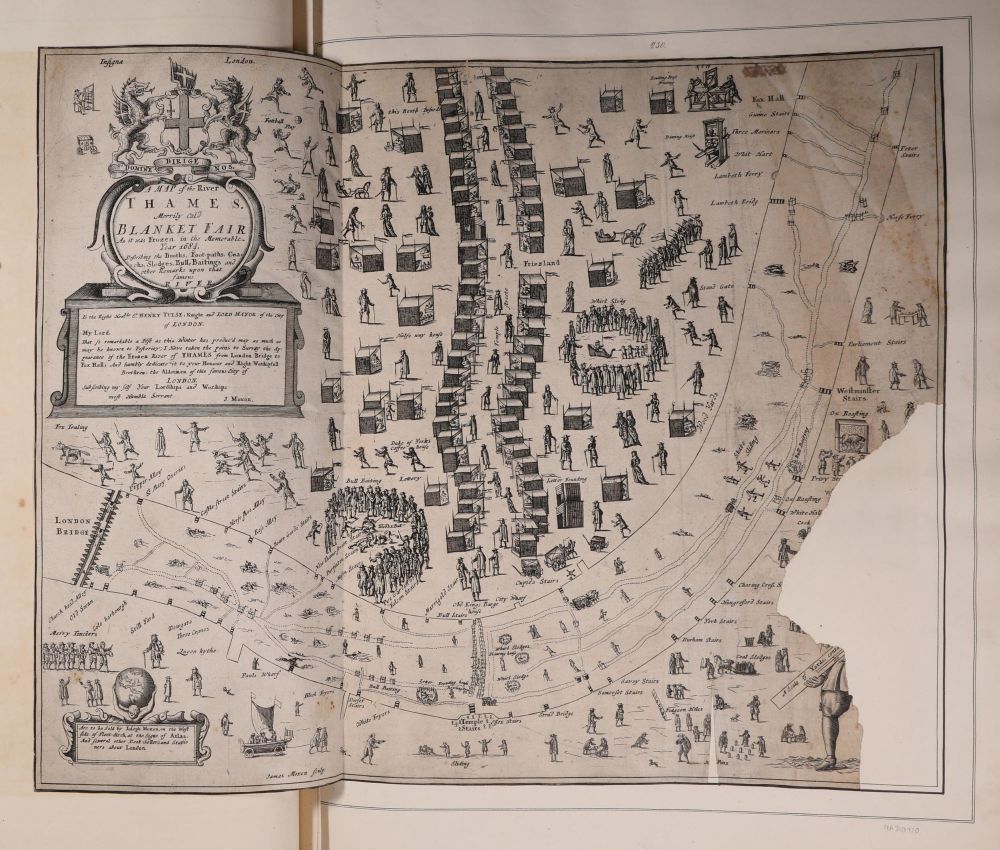

Air pollution only worsened after Evelyn’s time with the growth of London’s population and industry, reaching its peak in the 1890s. If one could ‘scarcely breathe’ during the 1600s, the complaints of winter lung ailments became common during this period of high pollution. This coincided with the huge growth in the number of international students that came to study at the Inn and some of them struggled greatly with the cold, damp, polluted climate in London. The Archive holds many petitions from students, accompanied by doctors’ notes, from the later part of the century requesting a remission of terms, allowing their early Call to the Bar and expedited return to a more favourable climate. One example can be found in the 1891 petition of Chandra Sekhar Sen Gupta (sometime written as Sengupta), a member from the sunnier climate of Agarparah, India. Suffering from multiple ailments, including chronic bronchitis, his doctor advised ‘he would be greatly benefitted by an early return to his native air and this severe season has aggravated his symptoms’ and Gupta requested a dispensation of two terms ‘so that he may not have to stay in this country another winter’. Unfortunately, his petition was not granted.

Doctor’s note for Chandra Sekhar Sen Gupta, 22 May 1891 (MT/1/PPE/7/175)

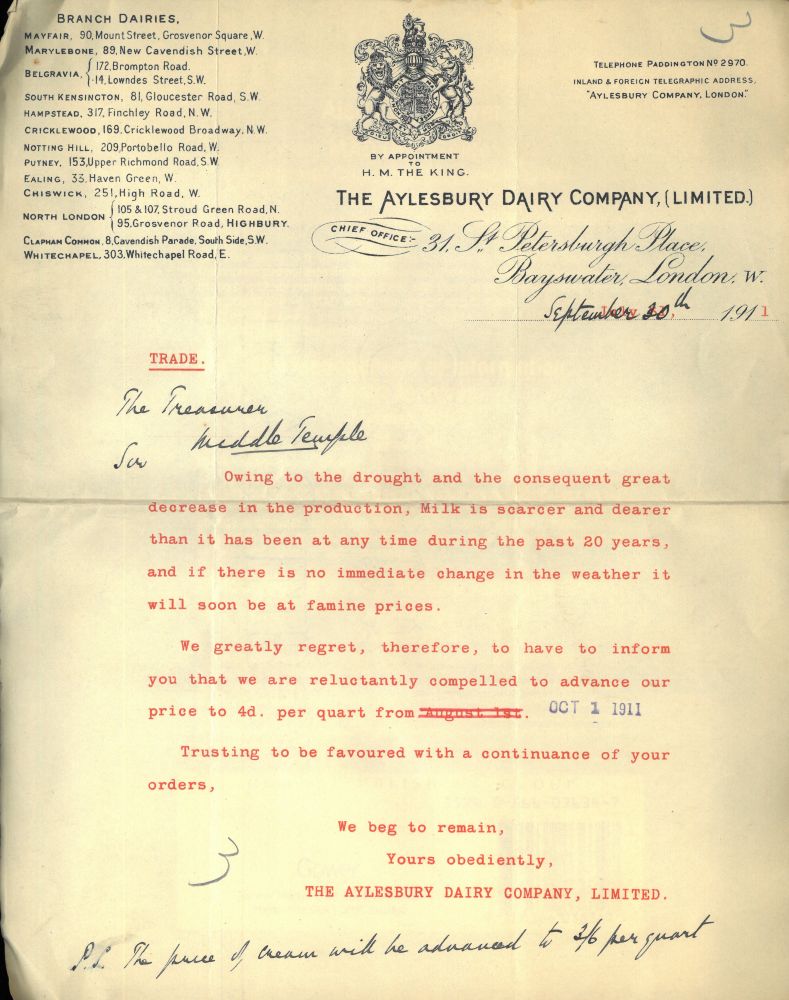

Although rarer than the cold and damp conditions usually endured by the Middle Temple’s inhabitants, periods of extreme heat and drought did occur over its history. One such instance was in 1911, which saw a heatwave beginning in mid-July, only ending in mid-September, with temperatures reaching a maximum of 36.7 ˚C. As well as impacting the Inn’s lawn and garden, the drought affected its supply chains. One letter from the Aylesbury Dairy Company Ltd., written on 20 September, informed the Treasurer that ‘owing to the drought and the consequent great decrease in the production, Milk is scarcer and dearer than it has been at any time during the past 20 years, and if there is no immediate change in the weather it will soon be at famine prices’. The price of the milk charged by the supplier went up to 3s. 6d. per quart, and this would have had a negative impact of the Inn’s finances for the year, especially if the price of other necessary commodities also rose.

Letter from Aylesbury Dairy Company Ltd. Regarding the price of milk after the summer drought, 20 September 1911 (MT/1/LIN)

By the late twentieth century, modern conveniences were able to mitigate some seasonal inconveniences. However, innovation could not fully insulate the Middle Temple from extremes of climate. On 15-16 October 1987 there was an infamous weather event, known as the ‘Great Storm’ that hit Britain. The severity of the storm was unanticipated by the authorities, leading to one of the most infamous media moments in British history where the meteorologist and weatherman, Michael Fish, dismissed a viewer’s concerns that a hurricane was on the way, telling his audience ‘don’t worry, there isn’t’. The country was hit with ferocious winds and eighteen people were killed during the onslaught. In this context the Inn escaped relatively lightly from the storm. Only several trees – an over 100-year-old plane tree, a smaller plane tree, a tulip tree and two flowering cherry blossom trees – were lost.

Photograph of a plane tree in Middle Temple Garden, felled by the Great Storm of 1987 (MT/19/PHO/10/17/15)

With increasing extremes of climate projected by scientists, it is likely that the Middle Temple will face dealing with future dramatic weather events. The precise form which these will take is unknown, but it will no doubt face these challenges with adaptability and resourcefulness. What is in no doubt is that the forever fluctuating national weather will continue to provide daily conversation for the members of the Inn for centuries to come.

Middle Temple Garden in the snow, 2022